I would like to dedicate this post to Angela Davis, a woman of a great strength and intellect, whom I have learned so much from and I have been lucky to meet once.

I would like to dedicate this post to Angela Davis, a woman of a great strength and intellect, whom I have learned so much from and I have been lucky to meet once.

“Are not Negroes* servants? Ergo! Upon such spiritual myths was the anachronism of American slavery built, and thus was the degradation that once made menial servants the aristocrats among coloured* folk…” (DuBois W.E.B. 1920:CH V).

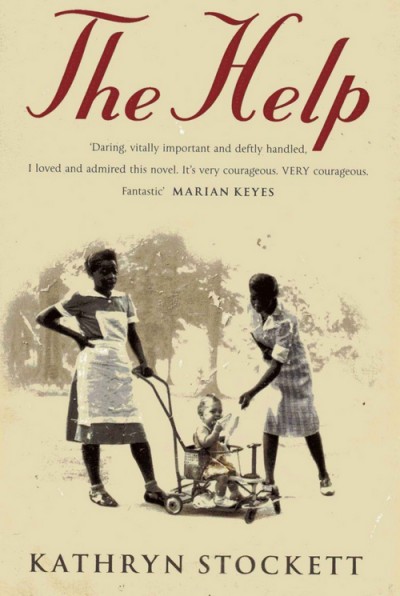

Thinking about “The Help” as a book and as a film adaptation took me a great deal of time. After watching the film for the first time two months ago, I got my hands on the bestseller by Kathryn Stockett and did not let go until I read it down to the last word as swiftly as my schedule allowed it. After the reading was done, I have seen the film twice. Some kind of strange drive to discover everything there is between the lines, both written and spoken, made me look into it over and over again.

During my studies, social rights movement was one of my Topics with the capital T. This became even more intense for me after reading “Women, Race & Class” by Angela Davis, which introduced me to many terrible faces of racism even in a greater detail. Therefore, my understanding of “The Help” is built upon this theoretic background.

In terms of literary form “The Help” can be hardly considered ground-breaking. First person narrative rotates between three major figures: Aibileen and Minny, two black maids at white households in Jackson, Mississippi, and Miss Sceeter (a nickname derivated from “mosquito”), a daughter of a wealthy white plantation owner family. The uniqueness of this book is, however, not in its literary form and even not in its main topic, which is hardly a revelation to anyone even slightly familiar with American history. It is in the private perspective of main figures towards the issues of racism and the aftermath of slavery. As the main characters are all caught up in the shell of their lives under the omnipresent racist hegemony, the narrative of the book follows them as they try to hatch out of it.

The central element of the novel is a book project by Miss Sceeter, which she is writing in collaboration with black maids. Pursuing a personal dream of becoming a writer, Sceeter makes an attempt to look beyond the constraints of the generally accepted rules, underlying the strict segregation in her home state of Mississippi. By channeling the black maids’ voices in her book and hence giving them a possibility to speak up about the drastic conditions of their work environment, Sceeter begins to realize how important and, at the same time, radical and dangerous her project is.

As the book project is progressing with more and more maids willing to take the risk of KKK-revenge for telling stories about their work at white households, Sceeter grows from emancipation-pursuing immature with nothing more than a personal glimpse into the maid-mistress relationship from her own household into a revolutionist, who is willing to put up with social isolation in order to reveal the truth. What begins as just another projection of white-centristic thinking and pursuit of personal success turns into a struggle for a good cause. Each central character evolves in terms of self-reflection and emancipation. Stepwise, all three women develop a better understanding of the “big picture” of the segregated racist order they have been taking for granted. Aibileen discovers new strength in herself finally speaking up and telling the truth about her experiences with white mistresses. By writing for Miss Sceeter’s book project, she honours the legacy of her late son Treelore and, at least partially, realizes the right for self-determination which, just like many other fundamental human rights, has been taken away from her and millions black men and women since the establishment of slavery. Minny finally finds a good household to work at and escapes the repression of her abusive husband. Miss Sceeter makes first steps towards her new professional life as an editor in New-York. Even if their book project does not necessarily change the situation for black women labouring at white households in Mississippi, to some extend it reshapes their personal lives empowering them for a new self-definition.

There is one more credit I would like to give this book: the one for the perfect language choices. While the book is very readable and certainly has that undescribable bestseller quality, it is the language of characters what makes it truly come alive. One can literally HEAR the figures speeekin’ in their accents, intonations, vernaculars. It is like music, like blues in one’s ears, and it makes the book very authentic.

Both the book and the film “The Help” are absolutely worth attending to. They will take you to the candy-coloured pseudo-paradise of the mid-60s Mississippi: to the world of polished families, desperately smiling housewives, false tranquility and pretended charity in the midst of which there is a huge dreadful (may be an L-shaped) crack neatly covered by a shiny silver plate.

In the afterword to her novel Kathryn Stocket admits to the mixed feelings towards her home state: “Mississippi is like my mother. I am allowed to complain about her all I want, but God help the person who raises an ill word about her around me, unless she is their mother too.” And that is, to my mind, the quintessence and the beauty of “The Help”: not so much objective, not at all absolute, but private, personal truth in its sincerest form.

* original vocabulary of the source. I apologize if someone finds it inappropriate.

Leave a Reply